A Day of GPR at Zorita Castle (Part 2 of 3)

Having climbed the zig zagging path from the idyllic village of Zorita De Los Canes up to Zorita Castle numerous times, I was ill prepared to do so in freezing weather and accompanied by a rather curious, unpleasant smell. In 2022, one of the watchtowers on the exterior of the castle collapsed, making the primary path between the village and the castle unusable. Since that occurrence, the castle grounds were shut down to the public and apparently this included the maintenance staff as well, as the grounds quickly became overgrown. In preparation for the Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), the grounds needed to be cleaned up. Luckily, Catalina and Dio, the onsite archaeologists, came up with a brilliant solution. A couple of phone calls and a herd of sheep came to the rescue. Sheep, similar to goats, eat just about everything and they left the ground largely barren with the exceptions of a rather healthy dosage of sheep poo and one hearty type of bush that apparently is not even palatable to the most unscrupulous eaters. It was that odor that blanketed the pathways as we ascended to the castle.

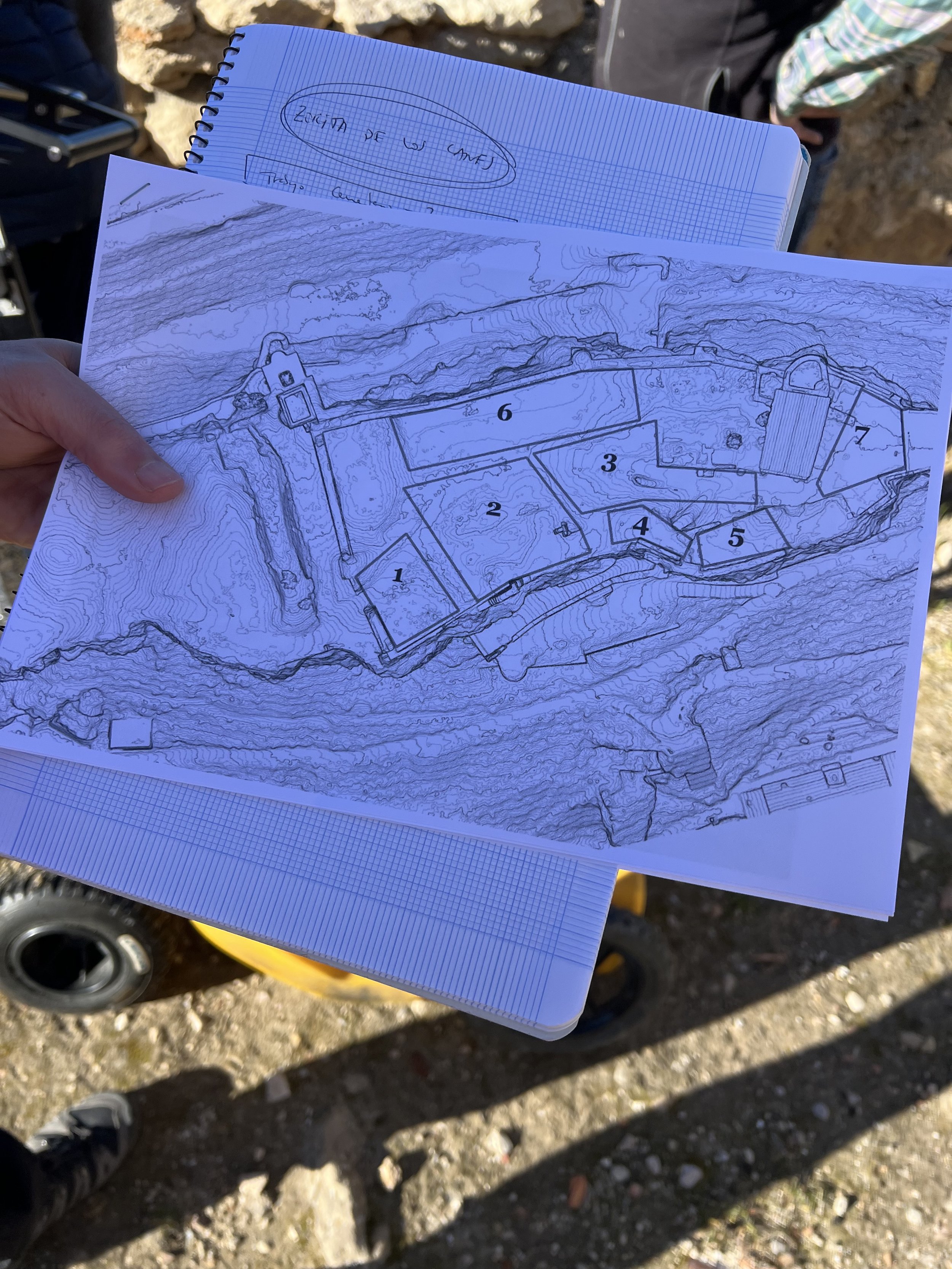

At 9:30 in the morning, the GPR specialists from Valencia University met us and assessed the situation on how to best approach the survey. A plan was hatched and reviewed to ensure every possible inch of terrain that could be surveyed – was surveyed. But we had a problem. Those branchy little bushes the sheep left behind… had to be removed. So, for the rest of us, the first order of business was to clear off those bushes with hoes we borrowed from the town. Nothing better than tilling the earth in freezing weather surrounded by the pungent smell of sheep droppings. Needless to say, we won’t be naming a beer after this experience!

From what we learned, GPR operates most proficiently on a flat surface. Weeds and other obstacles can be maneuvered around, but this impacts the survey’s results. The GPR system looks a bit like an oversized lawnmower with a huge antenna jutting upwards and a cord attaching it to a computer. It is pushed over the ground like a lawnmower shooting waves into the ground and receiving them back. Meanwhile GPS identifies the precise location of every reading. This allows each measurement to be sewn together to build a compete grid of what lies below the surface. When the ground is flat without above ground obstructions, a 3D image of what is below the ground can be created. However, the ground around the castle is littered with rocks and walls from structures lost to the ages. This forced the team to navigate around obstacles to get maximum coverage of the site.

The aim of the GPR survey is to identify subterranean rooms and other structures buried beneath the ground. This information is invaluable as it reduces the number of test trenches required to identify key areas for excavation. We can simply focus on the high value targets. The GPR unit we utilized typically delivers a good picture below ground of up to 4-5 meters or more depending on the composition of the sole.

Fortunately for us, the team from Valencia University were true pros. They knocked out the survey faster than any of us expected. We eagerly inquired as to the results. What did they see? Were there rooms yet to be discovered? Unfortunately, they were not ready to share. Due to the bumpy ground and the littering of old walls and various other structures, the data would require a significant amount of analysis. Inside their labs, the data would be pieced together, viewed through a host of lenses to allow an accurate interpretation of the data gathered. This process could take a month or two depending on competing priorities and their overall workload. We would have to wait… and as the late, great Tom Petty says, “The waiting is the hardest part.”